We Have More Power Than We Recognize

August 4, 2022

We Have More Power Than We Recognize

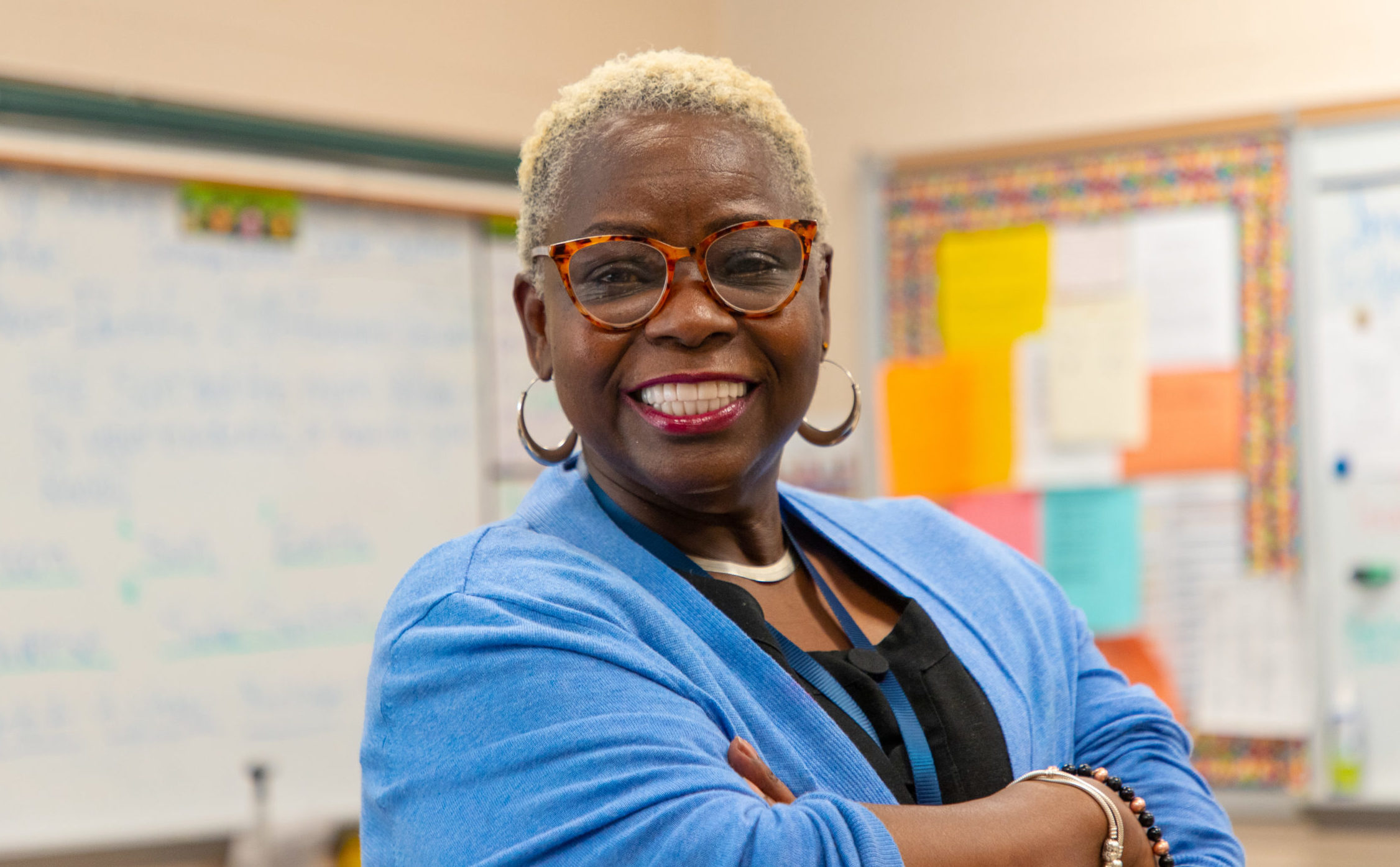

By: Jacqueline Person

Jacqueline Person, a recent Power Building Academy and Chisholm’s Chair alum, as well as a recently retired teacher from St. Louis Public Schools, stands in her former classroom. “I decided to pursue being a teacher…so I could have a lot more interaction with the kids and influence them in a positive way.” Photo by Nyara Williams.

You don't know what I'm going through, and at the same time I don't necessarily know that you don't know what I’m going through. It’s complex, right? There’s so many dynamics and intricate details that go along with people: why they do what they do, and why they may not be able to do any given thing at any given time. We’ve got to keep that sense of possibility open for others. We never know the trajectory or possibilities that are available to a person.

Growing up I always felt valued by my mother and father, but not necessarily by society. At school I got picked on because of my dark complexion, so I had low self-confidence and felt like I wasn’t good at much. But at home I was celebrated a lot. At my dad’s, he’d call me a “pretty good chocolate baby” or “chocolate pudding” and things like that, and at my mom’s I’d get a lot of material rewards. I was one of the best-dressed kids in school. I was pseudo-popular back then—not because of sports, grades, or boys or anything–but because I dressed well and my house was the party house.

“You never know the trajectory or possibilities that are available to a person, and you’ve got to keep that sense of possibility open for others.”

My mother was well-known in the city of St. Louis. She was a notorious drug-dealer for everyday people, preachers, lawyers, doctors, and politicians alike. She was also an incredibly giving and loving person. She would buy food for folks who needed it, help people pay their rent when their money was short, and build genuine community with everybody. She was never fake, didn’t hide her lifestyle, knew her values, and didn’t take no mess from anyone.

Later in life, I learned that in high school my mother was valedictorian of her class, a math wizard, and could type 150 words per minute. I never found out what changed for her, and why she got involved in dealing drugs. I asked one time but she couldn’t explain it to me. I did know, however, that through all of her phases, she was like Robin Hood.

Through my mom I was introduced to many different lifestyles that, well, the average mother probably does not introduce their daughter to. It was really stressful and intriguing at the same time. She’d be away for 2-3 days at a time, and the doorbell would ring at any hour–it was so erratic. Growing up, I had a lot of animosity towards my mother, yet I also learned so much from her. My oldest brother and I lived with my mom until we were like nine or ten, and then my father got custody of us when my mother went to prison for her “illicit activity,” if you will.

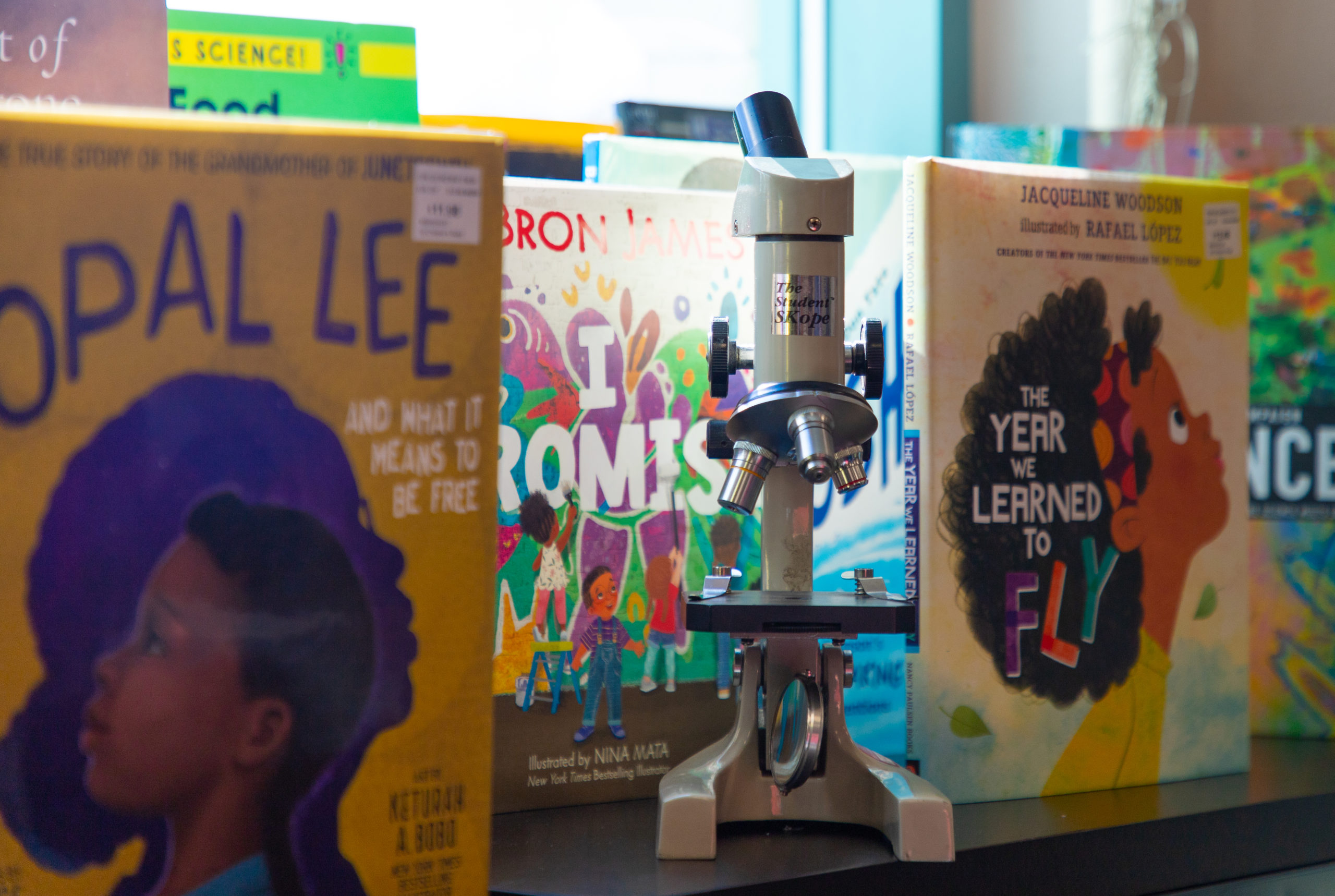

A window into the resources that Ms. Person filled her classroom with. Photo by Nyara Williams.

My father was a hard-working man. He worked two jobs to take care of us. He was a working alcoholic like many other Vietnam veterans, and he worked every day. He was the ideal father as far as I knew, besides the violence with his wife. And in my father’s home there was a lot of violence between him and my step-mother. A lot–and my big brother and I would run away all the time. We’d go swimming in the park on these outings and pretend life was normal, not understanding what traumatic life experiences we were going through. And then we’d run all the way to my mother’s sister’s house who lived really far away and stay there for a while at a time.

My big brother really took care of me. But at my dad’s, I couldn’t handle all that violence. That noise was just—it made me realize that I would never want to be in a relationship like that. We both went back to live with my mother; first my brother went, and then a year later I joined him when I was 16.

When I was growing up I’d steal stuff and sell some “illicit” things, too. Stupid stuff, you know. I didn’t need to do any of it, and I don’t even know why I did it. But I did. One day in my junior year of high school–coincidentally the same day that my mom was at court for another trial and all my family members were with her, including my big brother–the police came to school for me.

A while back I had gotten a traffic ticket in Jennings, one of the more racist areas in St. Louis county at that time, and I had ignored it. So that day while I was in English class, a city police officer came into my classroom, got me, and said, “Sweetheart, we’re just gonna take you up here to the local station to call the county station and get you a new court date.”

That was not all that happened. Once getting to the city police station, they stripped me and had a Black matron do some intrusive things to me all while I was on my period. I felt so embarrassed and scared. They put me in a cell with other women who kept saying things like, "You've been here before and you'll be back again." Then after a while, the police came back and told me, “I’m sorry, we’re gonna have to lock you up. The county police want you to be locked up and they’re gonna come and get you.”

I don’t remember if it was spring or fall then, but it was cold. And when the Jennings police officer came to get me, he handcuffed my hands behind my back, put me in the back of the car and rolled down the highway with all the windows open. I was scared shitless. When we got to the Jennings police station, all these white policemen were looking at nude magazines and I got even more frightened. They fingerprinted me, took a mugshot, and locked me up until my mom was able to find me later that night. It’s the only time I’ve been locked up in my life, and supposedly for just a damn traffic ticket.

“It’s the only time I’ve been locked up in my life, and supposedly for just a damn traffic ticket.”

The day’s experiences, mixed with experiences of visiting my mom in prison and having to be searched, intimidated, and demeaned by White folk was enough for me to decide that I would not have a life of crime. I told myself, “I aint’ ever going to jail. I’m not gonna have people belittling me. I choose to live beyond my past and present circumstances. This will not be the trajectory of my life.”

“Students need to be able to see other possibilities for themselves no matter where they’re coming from, because the possibilities exist.” Photo by Nyara Williams.

It was hard to switch my ways in high school. By then I had a well-established reputation of hardly showing up for class, selling stuff, and hanging with a certain crowd. I was able to do just enough to keep me out of the system. But right before I started my senior year, something intense happened in my mom’s world and she switched me to a different school for safety reasons. We had to give a fake address at the new school so I could get in.

Here, I didn’t know nobody and nobody knew me, and it was a new start of sorts. I started attending class and getting better grades. My parents both asked me, “why are you getting good grades here and not at the other school?” I didn’t know how to explain it. Eventually though, the school’s administration found out that we had given them a fake address and I had to leave and go back to my old school. I did a second senior year and graduated in five years.

“Students need to be able to see other possibilities for themselves no matter where they’re coming from, because the possibilities exist.”

After high school, one of my mom’s friends took a chance on me and gave me a job working at a health clinic, and that put me on a whole new trajectory. It changed my surroundings, relationships, and I started feeling more adult-like. I became a certified medical assistant working in the clinic, moved to St. Louis University, and worked in billing, insurance, and later in the emergency room admitting people for over ten years. Through St. Louis University my college tuition was paid for, so I started going to school for social work. I wanted to help people.

In my first year of the social work program, I had an internship at a middle school that had a reputation of being notoriously bad. One day, I was working in the classroom and I watched a middle school student tell a veteran teacher that she was gonna kick her ass. This middle schooler was a young girl, and in her threat she referenced that she had just come from King school. I could just see how her mind was working: I come from King, the bad school, and that’s why I can kick your ass–’cause I’m bad.

Seeing this hit me a certain way. Students need to be able to see other possibilities for themselves no matter where they’re coming from, because the possibilities exist. After witnessing that event, I decided to pursue being a teacher instead so I could have a lot more interaction with the kids and influence them in a positive way. Growing up and coming from what I had come from, I had never thought I could be a teacher. But I saw differently now and it seemed possible, and I pursued it.

“You just never know the trajectory or possibilities that are available to a person, and you’ve got to keep that sense of possibility open for others.” Photo by Nyara Williams.

I switched my studies to focus on education, and it took me ten years to get that degree. I was the first person in my family who’d ever gone to college, and also the first one to graduate.

My dad died 17 days before my graduation ceremony and at that same time my mother was locked up. I still choke up thinking about this. Over the years I had changed so much, and it was my father’s work ethic and my mother’s giving personality and belief in herself that helped me to do what I did. To be as empathic and committed to giving people a second chance as I am.

In 2020 I retired from being a special education teacher in the St. Louis public school system for over 20 years. I chose that route because when becoming a teacher, I had two black boys of my own and the system was already looking to put them into special ed. So many kids who are in special ed. shouldn’t be there–black boys especially–and I wanted to help get those kids out to where they belong. And in the special ed. classroom, I wanted to introduce students to things that stimulate a desire for learning, belief in themselves regardless of what society says, courage, and the ability to speak up and out for themselves and others.

“So many kids who are in special ed. shouldn’t be there–black boys especially–and I wanted to help get those kids out to where they belong.”

New possibilities aren’t just for young people and students, either. My mom came home from prison when I was 31, and from there on out she had changed, too. She became well-known in her church as a devoted member, committed to being of service in all areas of the church including being an outstanding cook and frequently welcoming members to her home for Sunday and holiday meals. Her lavish high-profile life of crime was channeled instead into her running her own housekeeping business. She started getting opportunities to be in front of people that saw her in a new way and loved her.

It turned out that one of her housekeeping clients had a really powerful role in Barnes Jewish Hospital, and that woman ended up offering my mom a job as a respiratory technician. She took it, and from there on out she got yet another opportunity to influence people’s lives and give hope to so many. Now how many notorious drug dealers get jobs in major hospitals? You just never know the trajectory or possibilities that are available to a person, and you’ve got to keep that sense of possibility open for others.

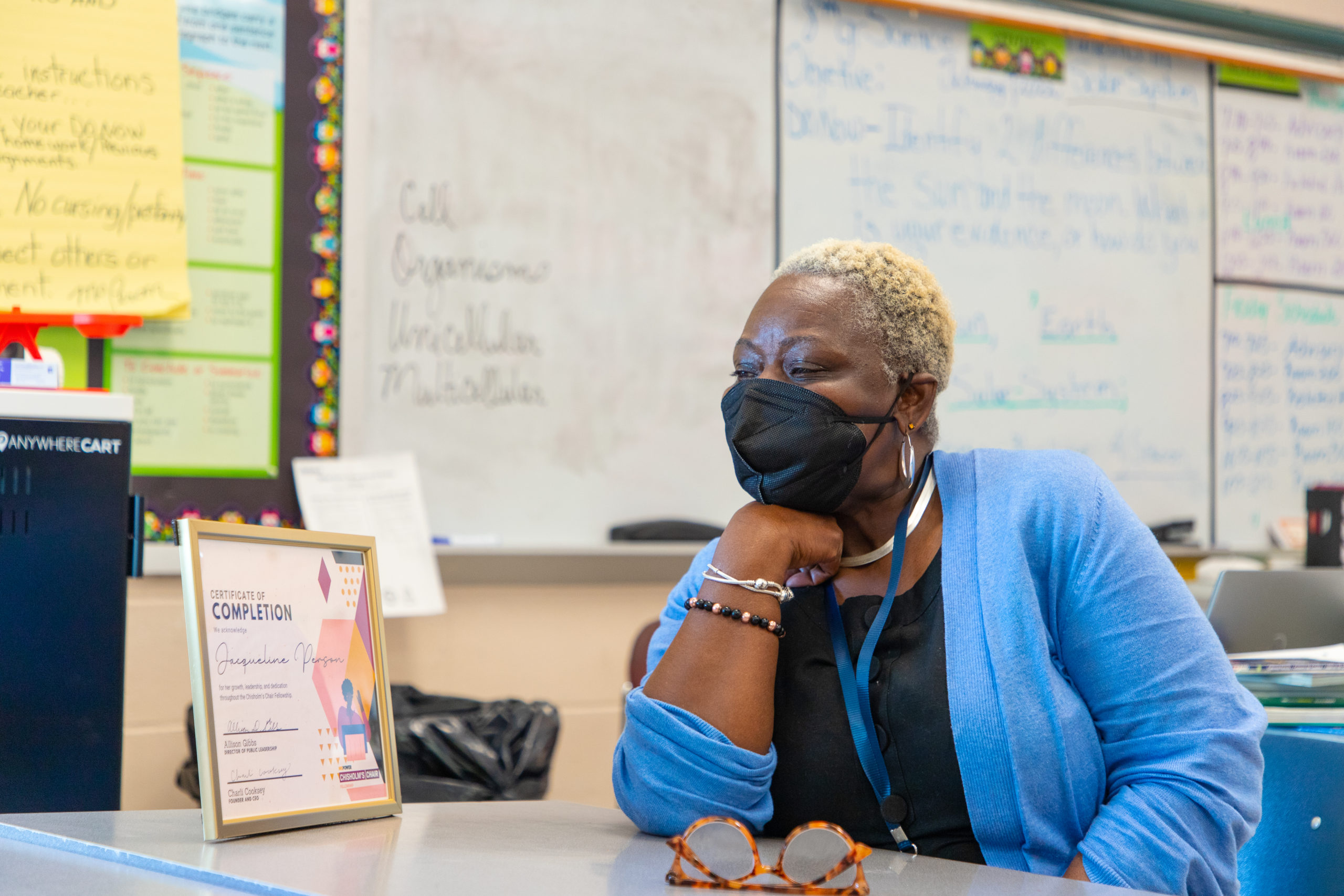

Ms. Person looks over her certificate of completion from WEPOWER’s Chisholm’s Chair Fellowship. “New possibilities aren’t just for young people and students….Even though I’m retired now, I am far from being done growing and helping my community bring out new possibilities.”

I used to tell my students all the time, “God gave you two ears and one mouth for a reason. Listen, listen, listen.” Listen to people authentically, and always see the best in them. If you approach every person with an optimistic attitude about who they are, that can open up huge and unforeseen possibilities.

I have experienced how there is power in numbers, and that we have more power than we recognize. When becoming part of supportive communities and relationships, so much can change. I was an inaugural member of the WEPOWER Power Building Academy in 2018 and recently went through the Chisholm’s Chair fellowship, a four-month WEPOWER program to help Black and Latinx women explore paths to elected or appointed office. Even though I’m retired now, I am far from being done growing and helping my community bring out new possibilities.

“I don’t have to be an ‘expert’ to speak up and have something valuable to say; my lived experiences and desires for the world I want to live in justify my speaking up.”

Among many things, Chisholm’s Chair has helped me to recognize that my voice, my experiences, and my hopes for our community are valid and valuable. I don’t have to be an “expert” to speak up and have something valuable to say; my lived experiences and desires for the world I want to live in justify my speaking up. And when I put my personal experiences together with other people’s experiences, they can create change and new possibilities. That’s when we can really hear each other, and we become more and more free.

Written in partnership with Whitney Bembenek.